Essay: Moment When a Singularity is Born: Essay on Motoharu Jonouchi (Go Hirasawa)

As part of the Japanese Expanded Cinema research, Go Hirasawa studied related footages that never made it into the Motoharu Jonouchi works “Document 6/15” and “Hi Red Center Shelter Plan.”

essay: Go hirasawa / 平沢剛

Moment when a singularity is born: Essay on Motoharu Jonouchi

1. Dokyument 6/15

When surveying the history of Expanded Cinema in Japan, it is important to discuss, first of all, the independent, avant-garde, and underground film movements that provide context and laid the groundwork. The first full-fledged new film movement in Japan began in the late 1950s. It primarily revolved around feature-length dramatic films and documentaries produced by major film studios, and avant-garde documentaries produced by educational film studios, as well as art films by a wide variety of filmmakers: students in university film study clubs, visual artists, photographers, musicians, designers, and 8mm movies by individual video artists. With the exception of the dramatic film group, most of these went on to be involved with Expanded Cinema. In this essay, I will focus on Jonouchi Motoharu, a leader of the avant-garde film movement in Japan, who experimented with expanding the medium before the term Expanded Cinema was coined. He was primarily based at the Nihon University Film Study Club (Nichidai Eiken) and VAN Film Science Research Center (VAN).

Motoharu Jonouchi, Document 6/15, 1961-1962, web preview version

Motoharu Jonouchi, Document 6/15 Related Film, 1961-1962, web preview version

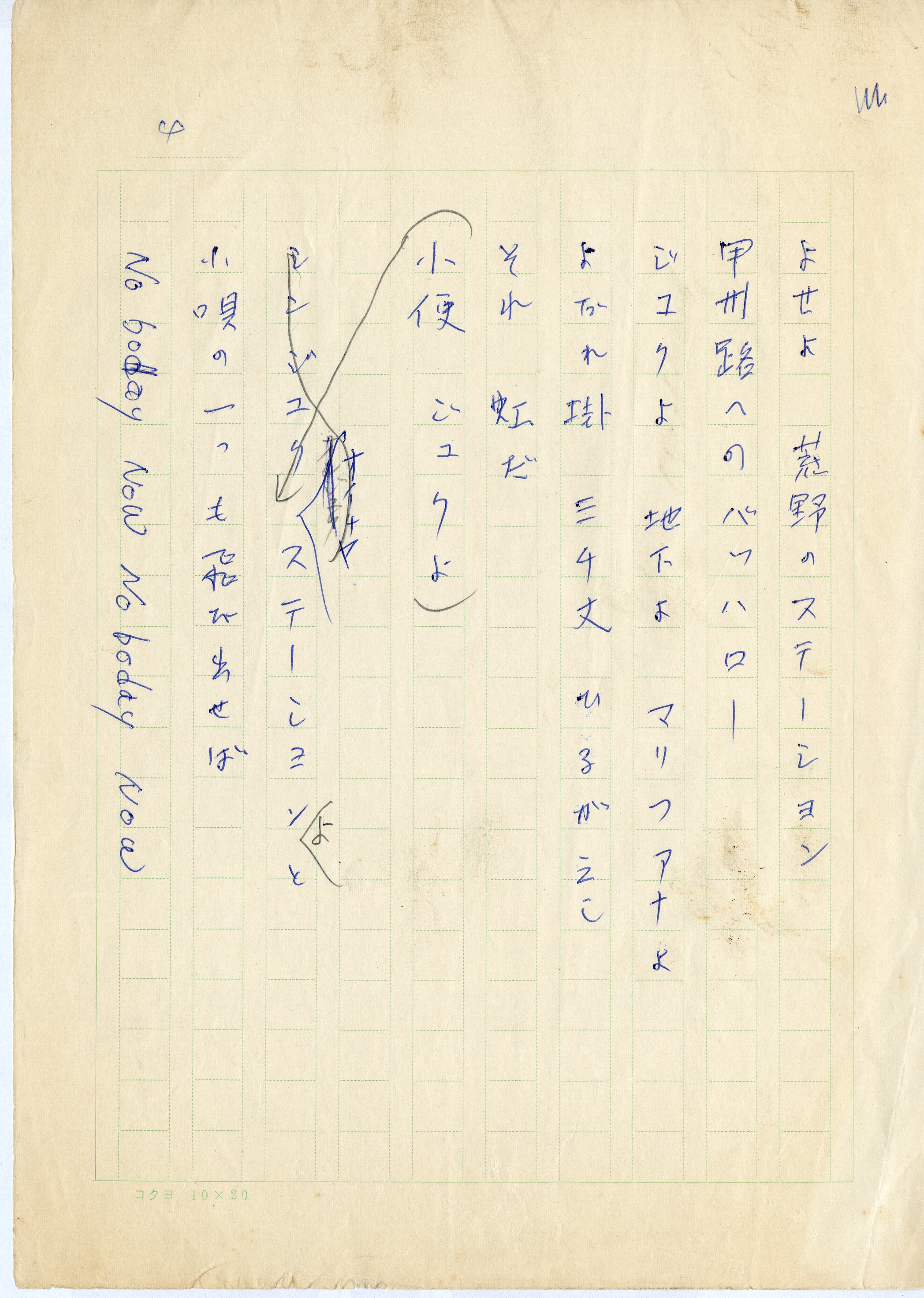

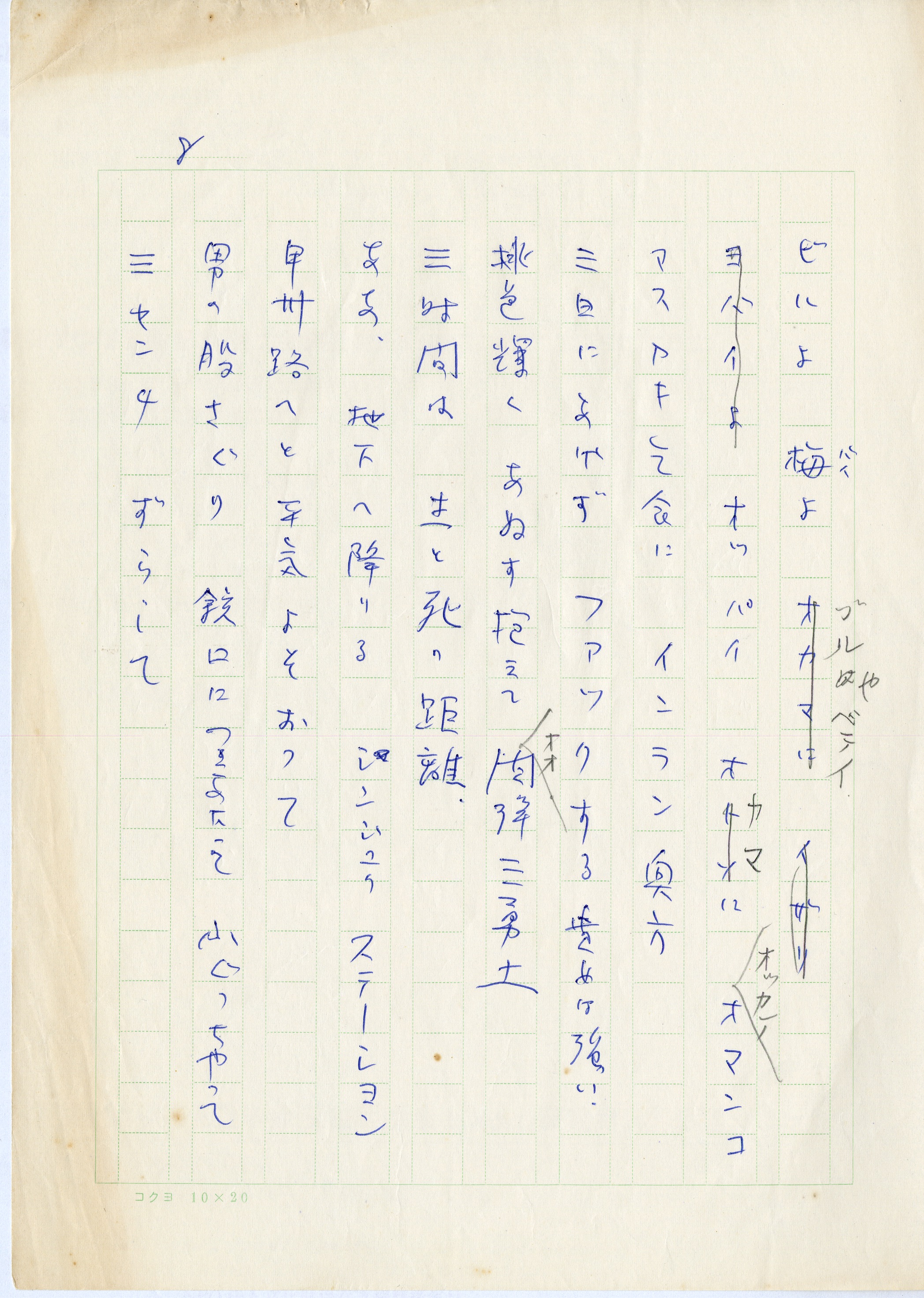

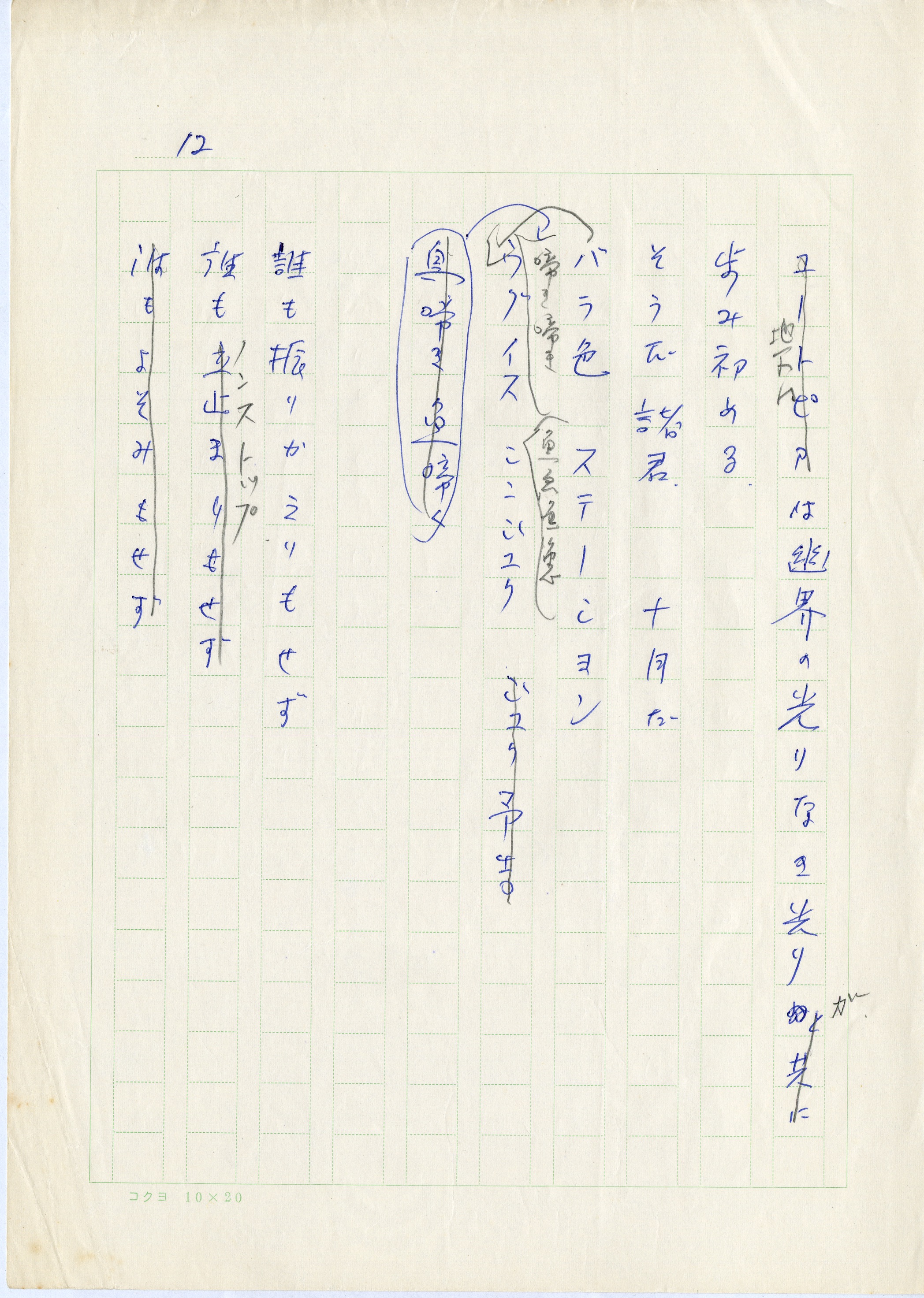

Nichidai Eiken, founded in 1957 by Katsumi Hirano, Hiroshi Kanbara, Hiroh Taniyama (Koh), Motoharu Jonouchi, and others, released Kugi to kutsushita no taiwa (Conversation between Nail and Sock, 1958), primarily produced by Hirano and Taniyama, followed by N no kiroku (The Record of N, 1959), documenting damage caused by the Isewan Typhoon (Typhoon Vera), primarily produced by Kanbara and Jonouchi. Then, during the campaign against the 1960 US-Japan Security Treaty, Jonouchi and associates fully participated in the protest movement while continuously documenting it from inside, rather than from an objective outsider’s perspective, and the film study club released the results as Pu pu (1960). Nichidai Eiken was reorganized into the New Film Study Club during the course of the Security Treaty conflict, and in the fall of 1960, Jonouchi, Kanbara, Naoya Asanuma, Keiji Kawashima, and Masao Adachi established VAN as a space both to live and to produce films together. VAN was a place where not only filmmakers but also people working in various media, including fine artists, musicians, photographers, and editors, could assemble. Out of this interaction emerged Document 6/15 ( Dokyumento 6/15, 1961-62), produced by VAN members as a documentary of the Security Treaty struggle, and was staged as a one-time screening performance.

The production and screening of Document 6/15 was commissioned by the All-Japan Federation of Students’ Self-Governing Associations (Zengakuren), for a memorial ceremony for Michiko Kanba. This public gathering, organized primarily by Zengakuren, both marked one year since the start of anti-Security Treaty demonstrations and memorialized the death of Kanba, a female University of Tokyo student killed during a demonstration in front of the National Diet Building in June, 1960. Judging by the intent behind commissioning the work and holding the gathering, we can imagine that Zengakuren expected a film documenting its movement via images of the demonstration in front of the Diet. However, Jonouchi and colleagues took the project in a different direction, seeking not only to screen a film, but also to carry out various cinematic or political experiments as a one-time-only event, to incite a major fracas.

In addition to footage of the struggle shot by Jonouchi and others, news footage, reenactments of violence by police and the rightists, and so forth, were inserted into the Document 6/15. In addition to moving images, alternating still photographs of Kanba’s face and devil paintings were projected, and the soundtrack, comprised of voices of the politically conflicting Zengakuren and Japanese Communist Party, simultaneously played on the left and right channels, as well as the original “Song of the Devil.” There were also elements of a happening, with objects suspended and balloons inflated in front of the screen, and the sound of the venue itself broadcast, accompanying a black screen. As the venue swelled with protests against the screening, which sorely betrayed political expectations, the organizers stopped the event and criticized VAN vehemently while apologizing to the participants. In fact, however, such political turmoil was VAN’s aim all along. One member of VAN anonymously commented, during the controversy over the screening after the event, on what they were attempting:

We thought this “work” would probably be a one-time-only event. We had never wanted to make a complete, perfect work to begin with, and for me at least, it is inappropriate even to call it a “work.” Light was shed on an invisible state of affairs, which encompassed Zengakuren as well. I believe that creating a certain “situation” was an essential part of the production.

This person defined VAN’s film as a one-off media event aimed at creating a new situation, not a work that was completed and then repeatedly screened. And by carrying this out in the literal “political space” of a political gathering, they advocated the autonomy of film/art from politics, and at the same time inquired about the nature of politics – in the narrow sense about Zengakuren, and in the broad sense about revolutionary movements – using the intrinsically one-time-only nature of cinematic expression. At the same time, Document 6/15 cast doubt on the standard model of a film screening, where a film is projected on a screen and the audience is expected to passively watch it, and raised formal and theoretical questions. In a later interview, Jonouchi described this work when looking back on the VAN years:

When someone said they had a chance of getting into a magazine, everyone would help out, and when Kanbara and I started working on this Security Treaty project, everyone joined in and cooperated. The Zengakuren (All-Japan Federation of Students’ Self-Governing Associations) BUND faction sponsored our documentary covering students’ meetings, but in fact we were the ones in charge of the meetings. Sometimes we even stage-managed them, in a way. With Bolex cameras in hand, we got into the crowd as if we were ready to fight, vulnerable to whatever might happen even as the cameras kept rolling. Of course, they were all in favor of bringing ideology into filmmaking, but we completely rejected the whole idea. We were working magic, invoking demons. [1]

The idea of placing pre-modern magical power in opposition to Politics with a capital P led to “Song of the Devil” and the devil painting slides, but it should be emphasized that in its prehistory, Expanded Cinema in Japan emerged not from aesthetic and formal experiments with film or film/art, but from raising the relational framework of politics and film/art. Today, Document 6/15 survives only as a few fragments of 16mm film, the sound and slides are lost, and there are no photographs taken at the venue. As the artists, including Jonouchi and Kanbara, are no longer with us, it is extremely difficult to reinvestigate the work. Not only was the event controversial when it was staged, but also, when artists and critics who belonged to or were associated with VAN looked back on the event, their accounts were all slightly different. This points to the difficulty of envisioning and understanding the happenings that unfolded both inside and outside the venue, and the entire course of the screening, which descended into such chaos that it had to be halted. Each occupying their respective positions, not even the participants knew all that was going on.

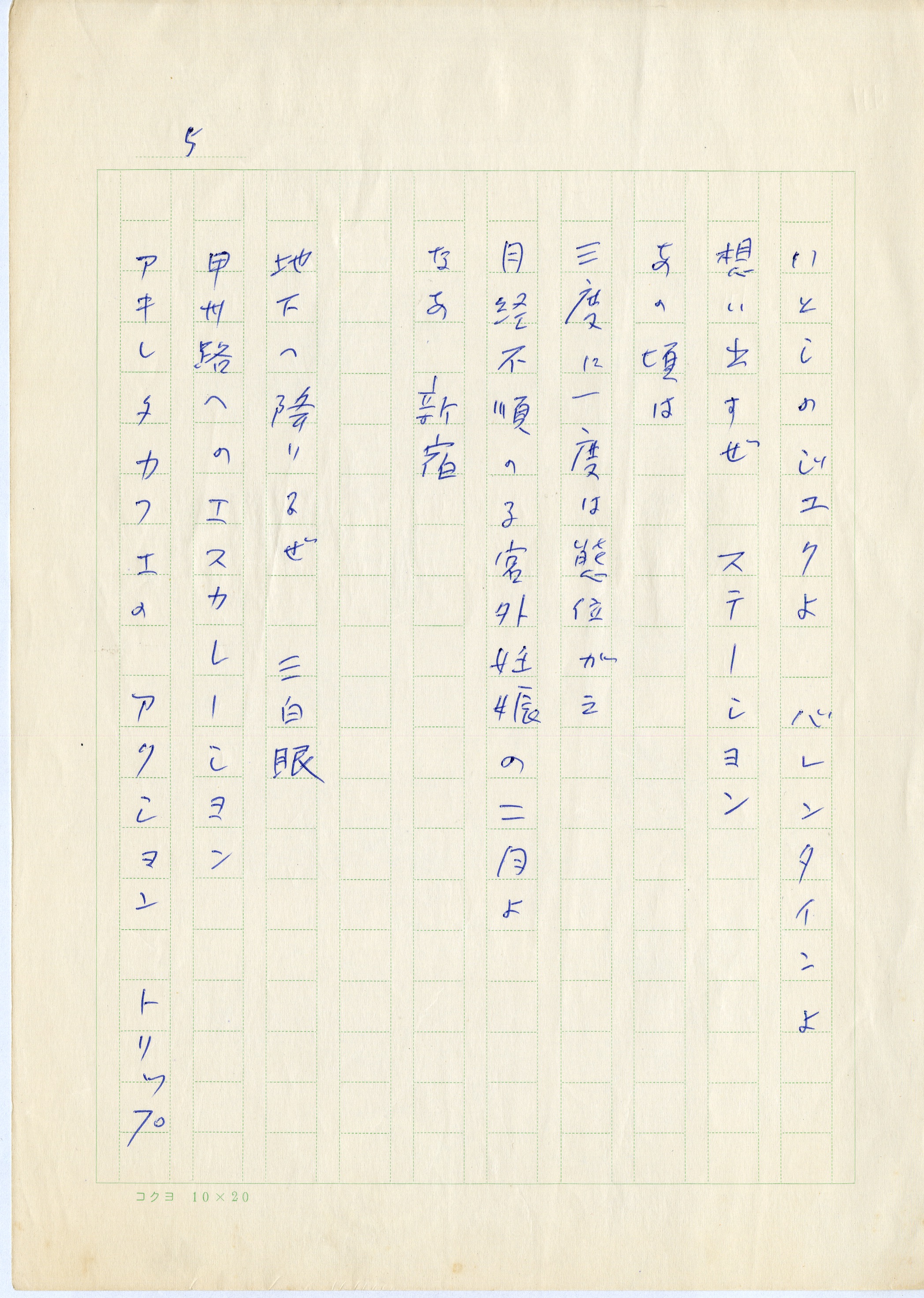

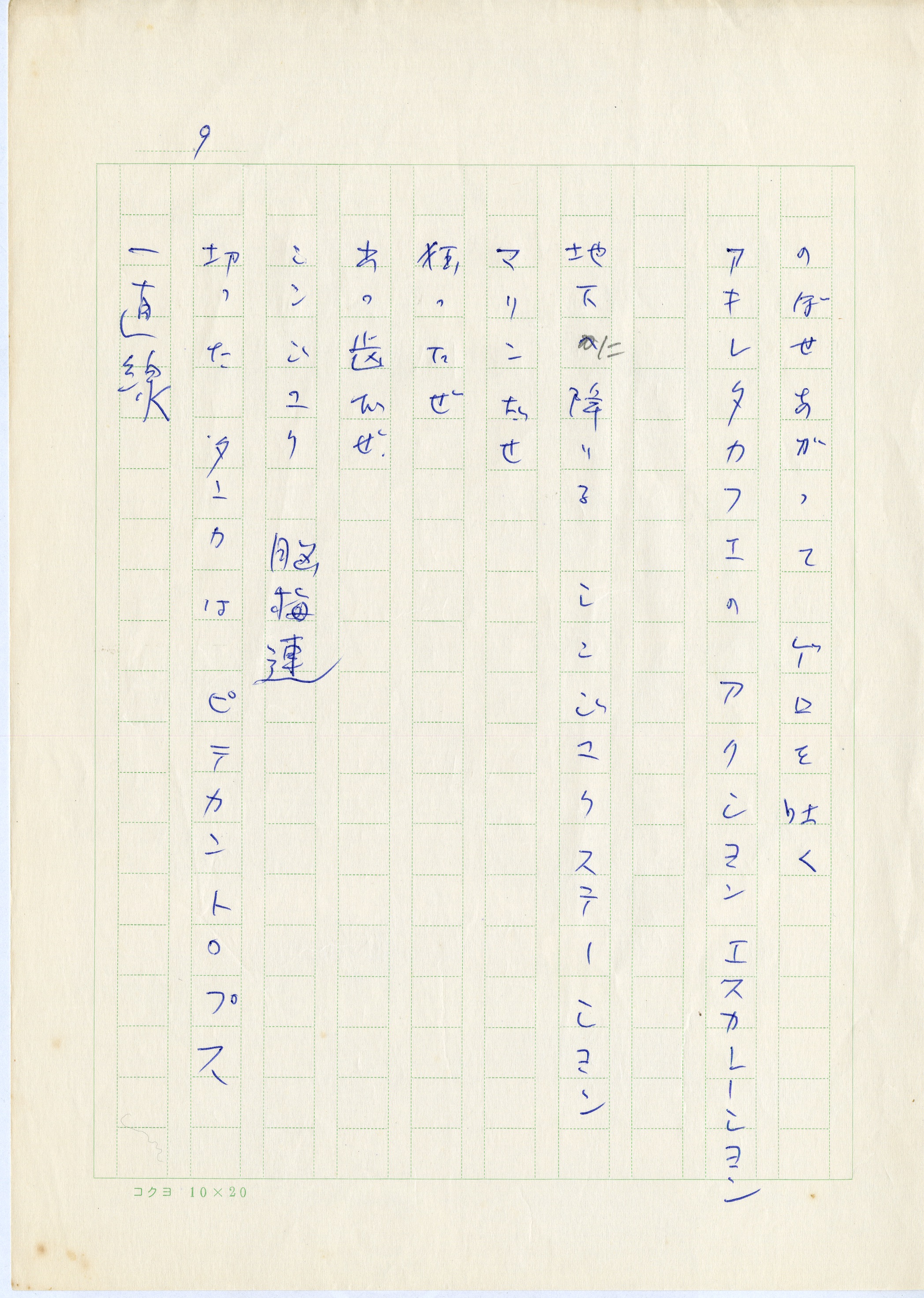

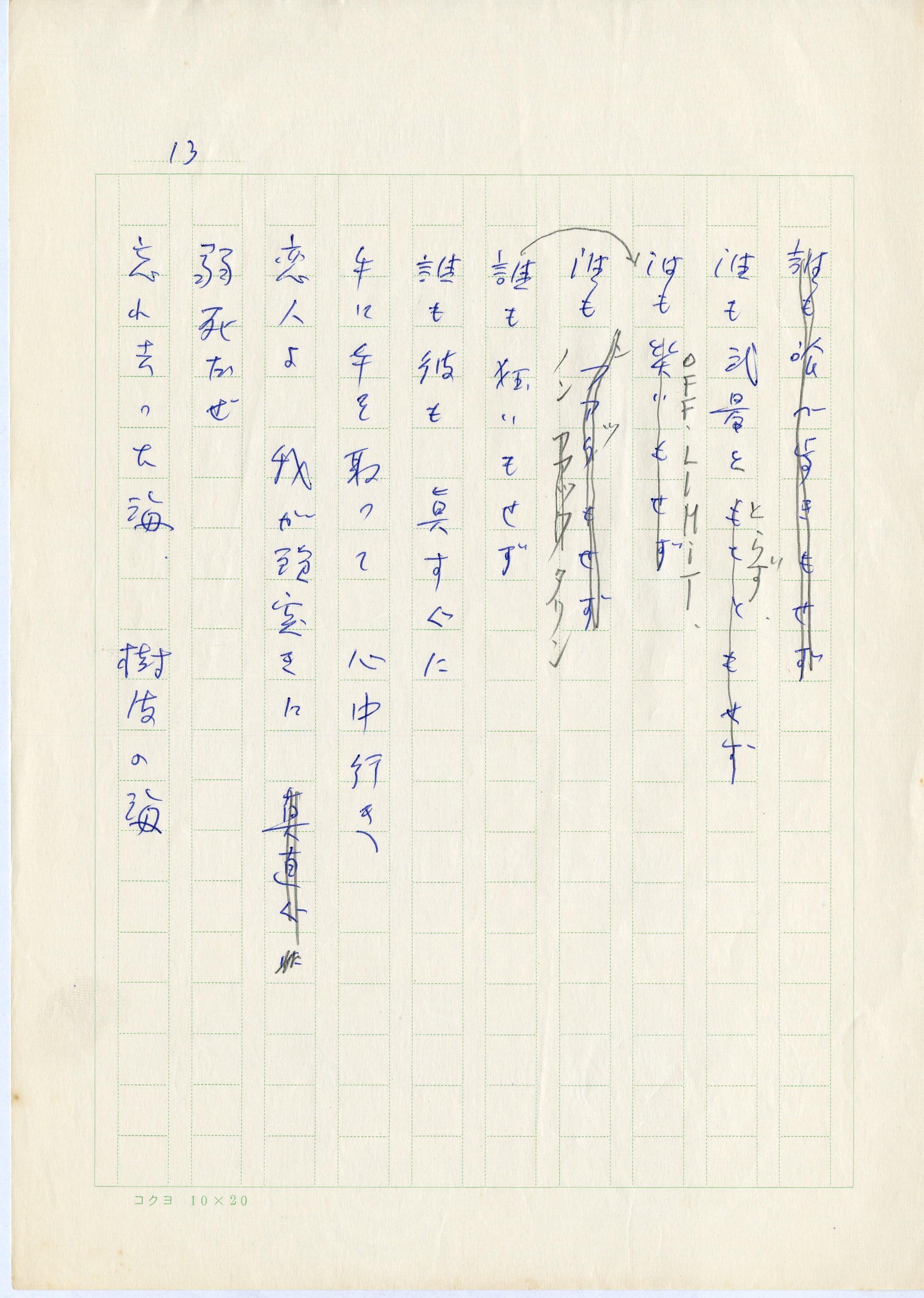

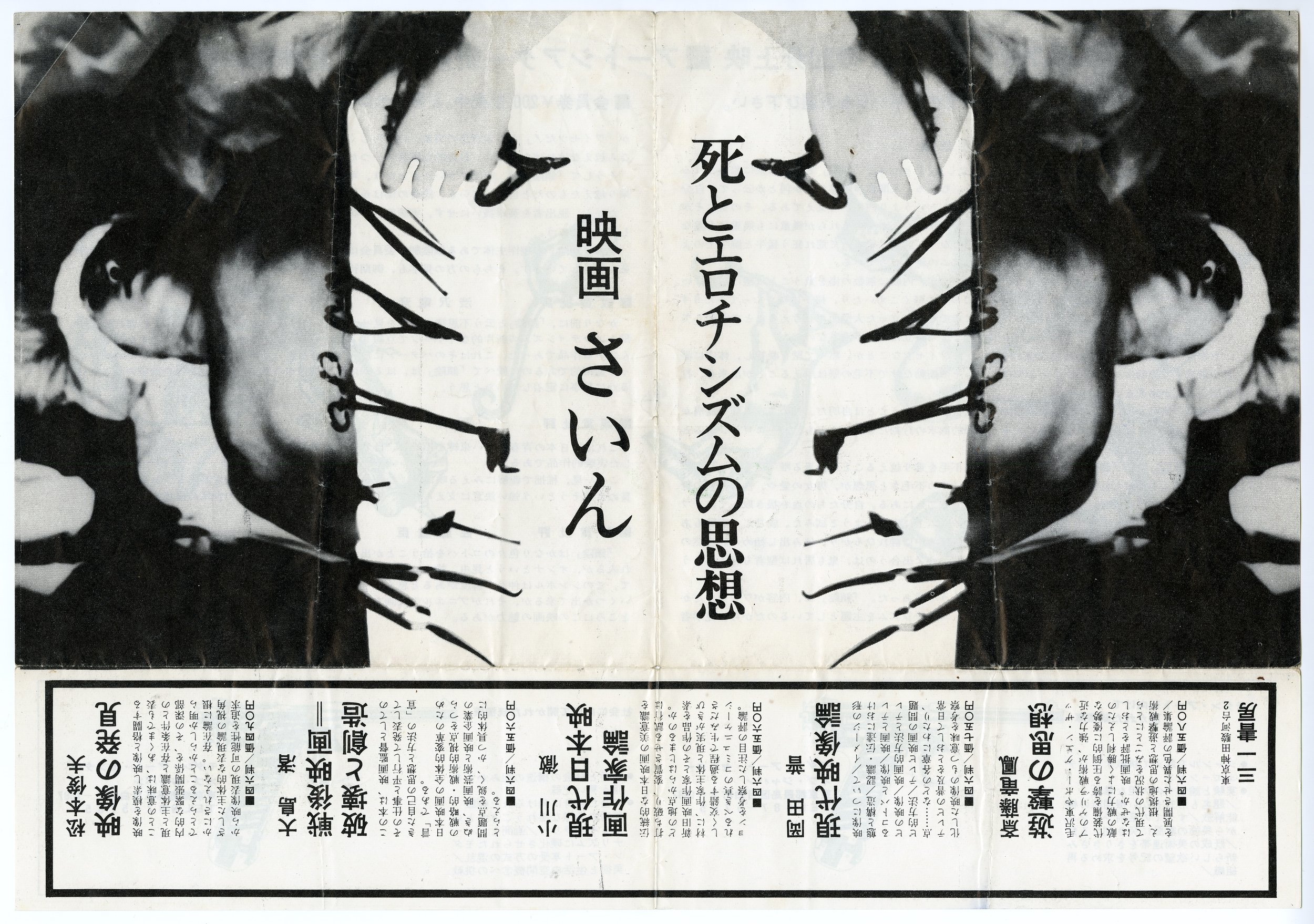

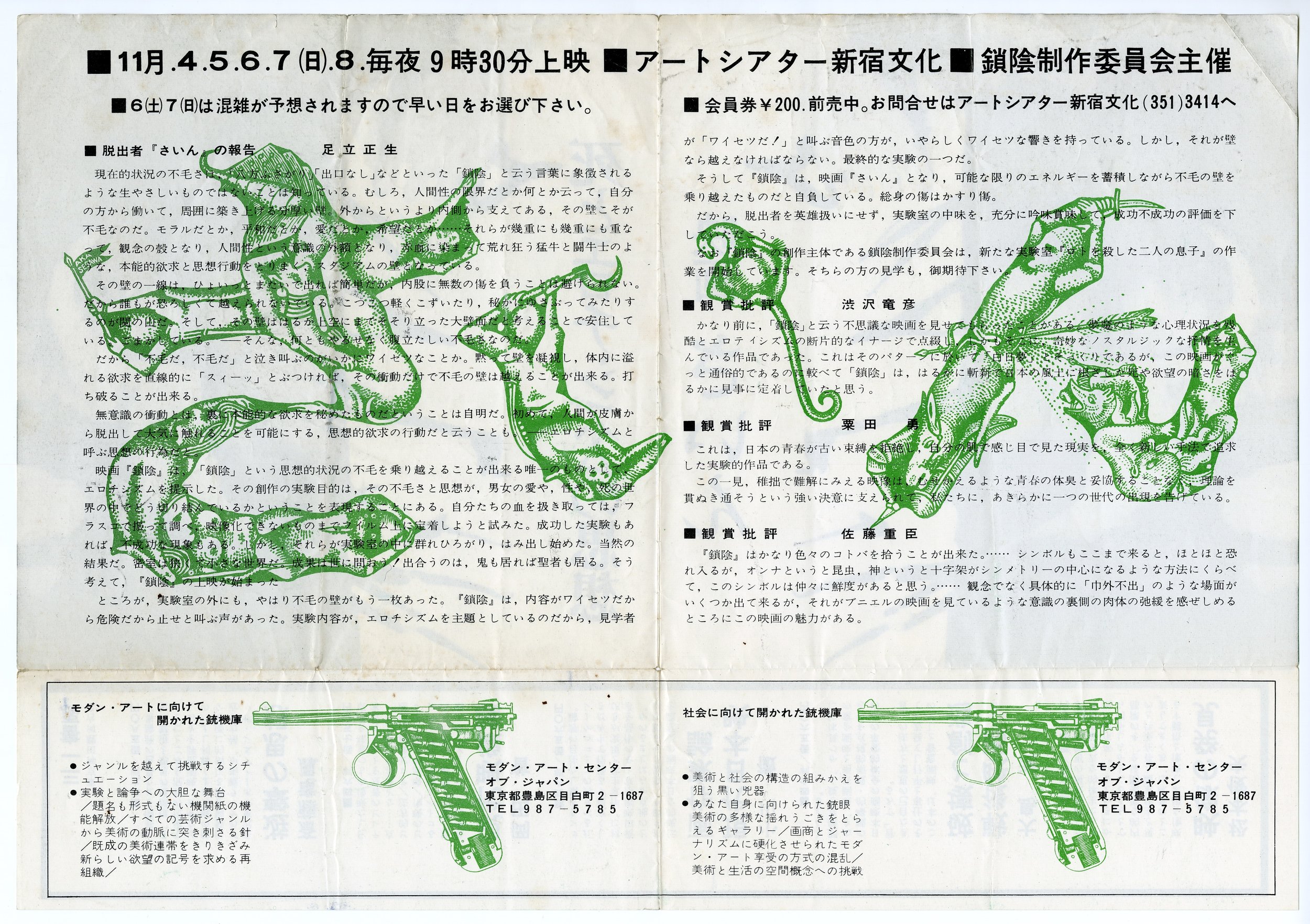

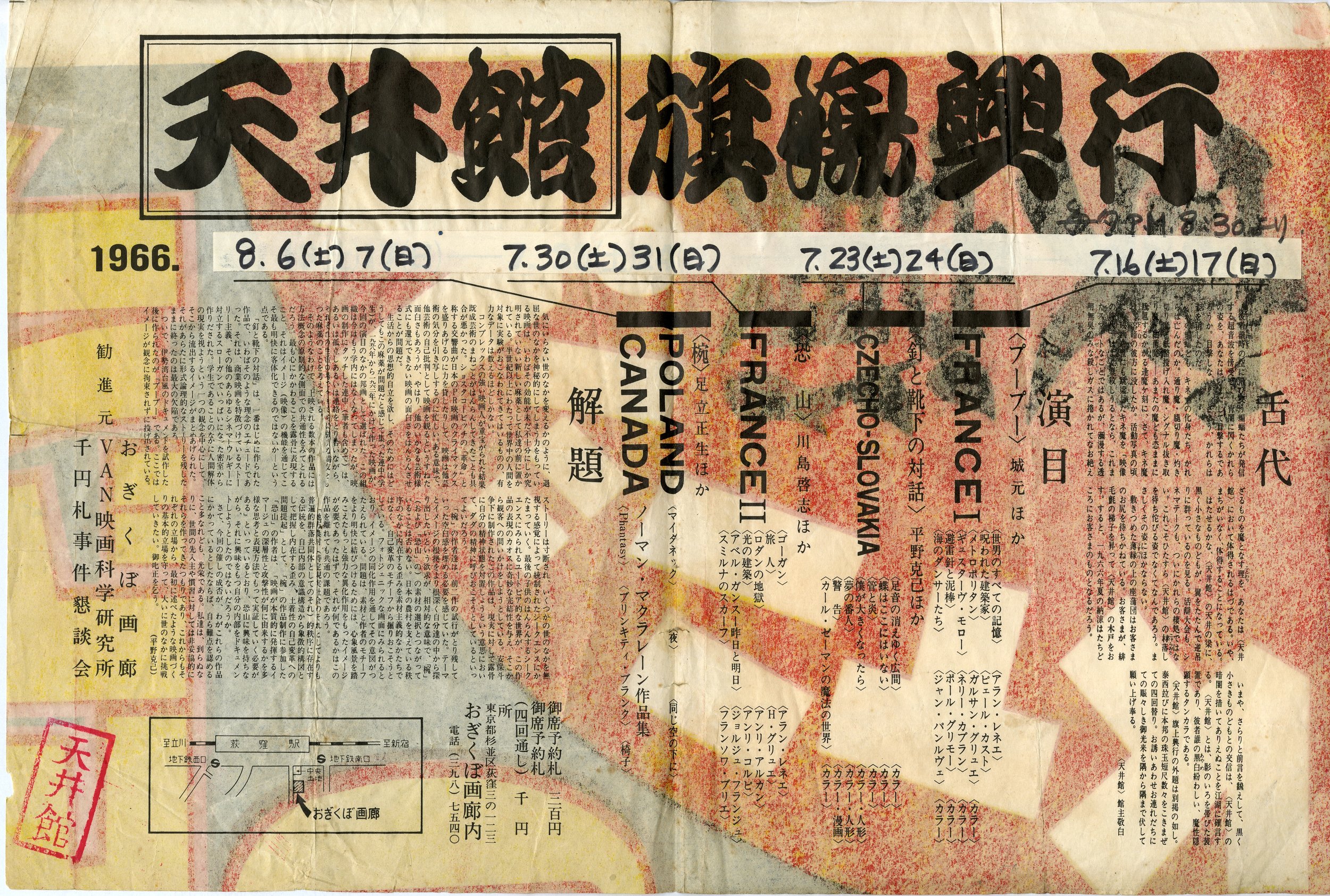

At a memorial rally at Kudankaikan in 1962, Satoshi Kitakoji of the Zengakuren leadership, who had lambasted VAN from the stage at the time of the 1961 gathering, participated in a repeat screening of Document 6/15 produced by VAN. There are even fewer existing documents or records than of the 1961 version. Tone Yasunao of the music collective Group Ongaku, who had been interacting with VAN, took part in composing, and Toshi Ichiyanagi, Takehisa Kosugi, Akemichi Takeda, Yoko Ono, and others, joined as performers. Such interdisciplinary experiments mediated by VAN were prefigured by the 1960 event Zero Deportment (Hiko Zero), and led to later events such as the 1964 Ritual for Closed Vagina (Sain no Gi), the 1965 Muse Week at Modern Art Center of Japan, the 1966 flag-raising opening event at Tenjokan, the 1967 Lunami Film Gallery at Lunami Gallery, and participation and planning of Intermedia events. Further, in terms of Jonouchi’s own work, this development led to making Shelter Plan (Sherutā puran, 1964), documenting Hi Red Center’s performance event of the same name.

2. Shelter Plan

Motoharu Jonouchi, Hi Red Center Shelter Plan, 1964, web preview version

Over two days, January 26-27, 1964, the Hi Red Center founders (Genpei Akasegawa, Natsuyuki Nakanishi, and Jiro Takamatsu) and Tatsu Izumi staged an event called Shelter Plan in the lobby and room 340 of the Imperial Hotel in Hibiya, Tokyo. Hi Red Center claimed to be acting on behalf of a fictitious organization, the Shelter Plan Conference, and sent invitations and instructions to specific acquaintances. When visitors arrived, they had their height, weight, shoulder width, face size, interior mouth volume and other measurements taken, and photographs taken from the front, sides, back, top of head, and bottom of shoes, generating data with which individual specifications were created for customized one-person shelters. No shelters were actually created, and the series of events – people receiving invitations, coming to the hotel as instructed, and participating in their own measurement – was the work itself. Hi Red Center was formed in 1963 with the mission of staging “direct actions,” and went beyond existing concepts of the work of art, repeatedly staging events and happenings not only at museums and art galleries but also on streets, rooftops, and trains. Shelter Plan was one of Hi Red Center’s most ambitious events, involving not only visual artists affiliated with Neo-Dada and Fluxus, but also musicians, designers, editors and filmmakers. [With an exhibition the previous year, 1963], Akasegawa had elaborately replicated a 1,000-yen bill, made copies of it and distributed them, in what became known as the “1,000-yen bill incident.” On January 17, the day the invitations to Shelter Plan were issued, the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department impounded his original copper plate [as evidence in a counterfeiting criminal indictment of Akasegawa]. On January 27, the second and last day of the event, the Asahi Shimbun newspaper reported the confiscation in its morning edition, and the event became one where art was not placed in opposition to politics, but integrated seamlessly.

Jonouchi and other VAN members documented this multifaceted, interdisciplinary event, with photographs of Hi Red Center’s works prior to the Shelter Plan and of the event itself, and footage of a shelter shot after the event and inserted into the rest of the film. This film conveys the overall flow of the event and the actions of the participants, but there is no sound and no explanations appear on the screen, so all is ambiguous unless viewers already know what they are watching. However, this reflects Jonouchi’s endeavor to bear witness to this strange, unfamiliar event with a film responding to Hi Red Center’s experiment in kind, rather than simply making an ordinary documentary. With techniques of repetition, he sought to recreate the one-off nature of the Shelter Plan event, or to create a new one-off event, while intervening in the medium of film-art as something to be appreciated and consumed by audiences. The direction, filming, editing, and screening were carried out in this paradoxical context. For this reason we are not sure when Shelter Plan in its currently known form was completed, though it seems to have been put together in 1964. There is documentation of it having been screened, in whole or in part, first in a courtroom as evidence during the “1,000-yen bill trial” of Akasegawa in 1966, and then during the three-day (February 13-15, 1967) second Lunami Film Gallery study group at Lunami Gallery, entitled VAN DOCUMENT. [2] When asked about the intent of the performance/screening, Jonouchi replied as follows:

It depends on the viewer. I want the work, the film itself, to have fluidity. So it could be something different today than it was yesterday, and then something else again tomorrow… I myself am not sure. (Note: On the first day, he recited poetry with a flashlight hanging from his neck. From time to time, he shouted instructions fiercely at the projector: “Film cut!” “Film start!” On the second day, he and a partner stood in front of the screen naked with their backs turned to the audience and moved about to the left and right. The film projected on the screen, the bodies, and the film projected on the bodies overlapped... On the third day, a timid-looking man repeatedly struck the screen as if with a whip.) [3]

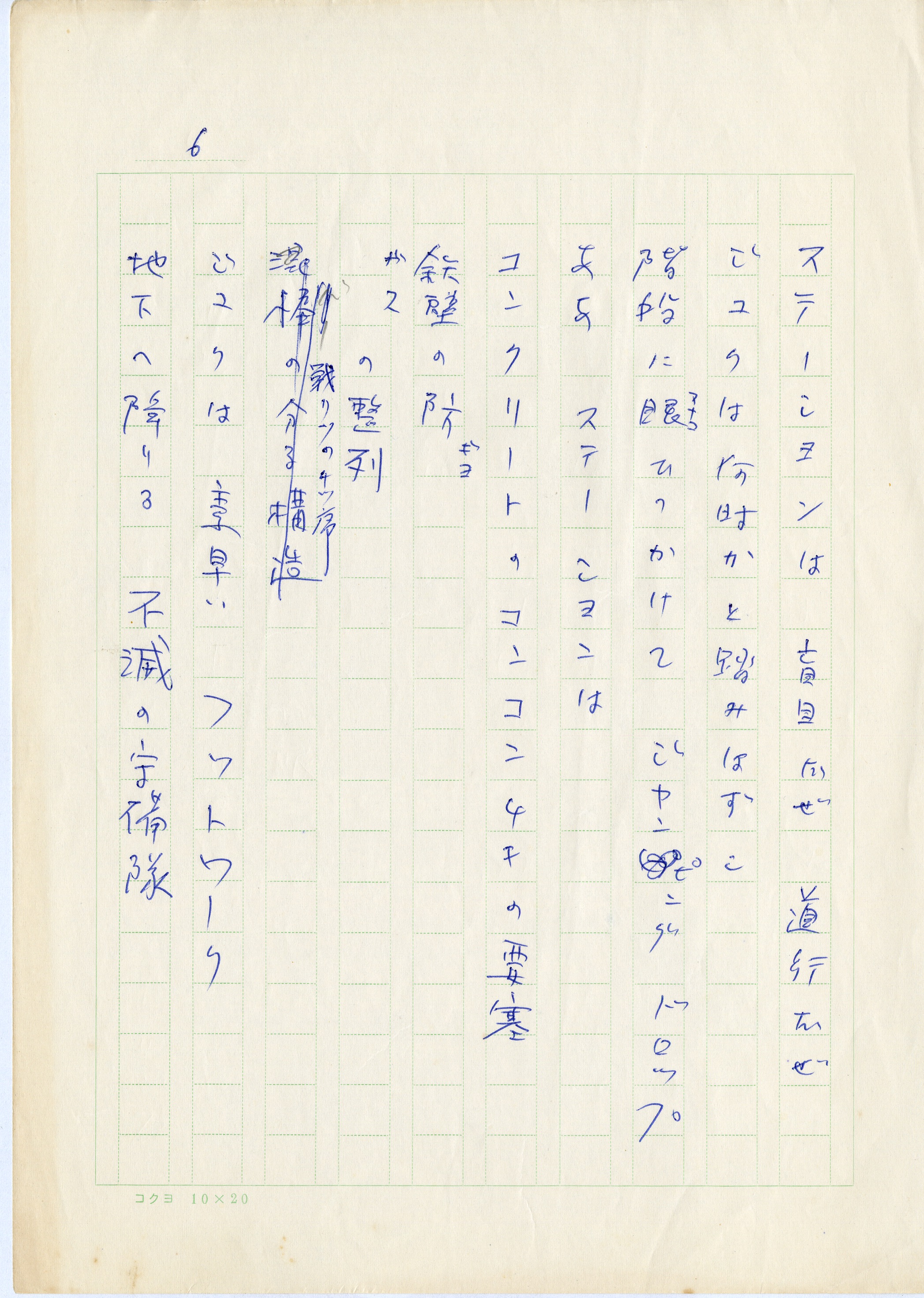

As the note added to this comment makes clear, a choice was made at the time to conduct various different Expanded Cinema experiments each time, rather than simply producing a finished work and showing it to an audience. In response to another question about whether he intended to organize the screen in any particular way, he said, “Absolutely not, I decide when I hit the projector switch, and various images overlap and expand… Never edit, is my motto.” [4] One can say that for Jonouchi, screening was a process of confronting the light and shadow cast on the screen and creating a new and different expression, while sharing the space with a different audience, each time. Of course, in Expanded Cinema and performance/screenings, the order of films screened and the content of the performances differ, so one could say the medium is essentially one-time-only in a formal sense. However, Jonouchi did not adopt this approach on methodological grounds, but instead threw himself body and soul into the moments when one-time-only happenings were generated, as if wagering his very existence on it. In 1967, Jonouchi captured on film the old Imperial Hotel [where Shelter Plan took place] in Imperial Hotel (Teikoku hoteru, 1967-68), prior to the demolition, due to aging and ground subsidence, of the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed building. Today, Shelter Plan is widely known as a precious moving-image document of Hi Red Center in action, but when screening it each time, Jonouchi repeatedly sought to make the performance/screening an event in its own right, and he also consistently turned his attention to the venue, the Imperial Hotel.

The Imperial Hotel was the site of an event by Hi Red Center, but I was also captivated by the hotel itself, mysteriously entranced by it in fact. I filmed it several times, including in a state of collapse. When I entered its corridors, I felt just like I was entering the pyramids or something. I thought I was entering the heart of the city itself. [5]

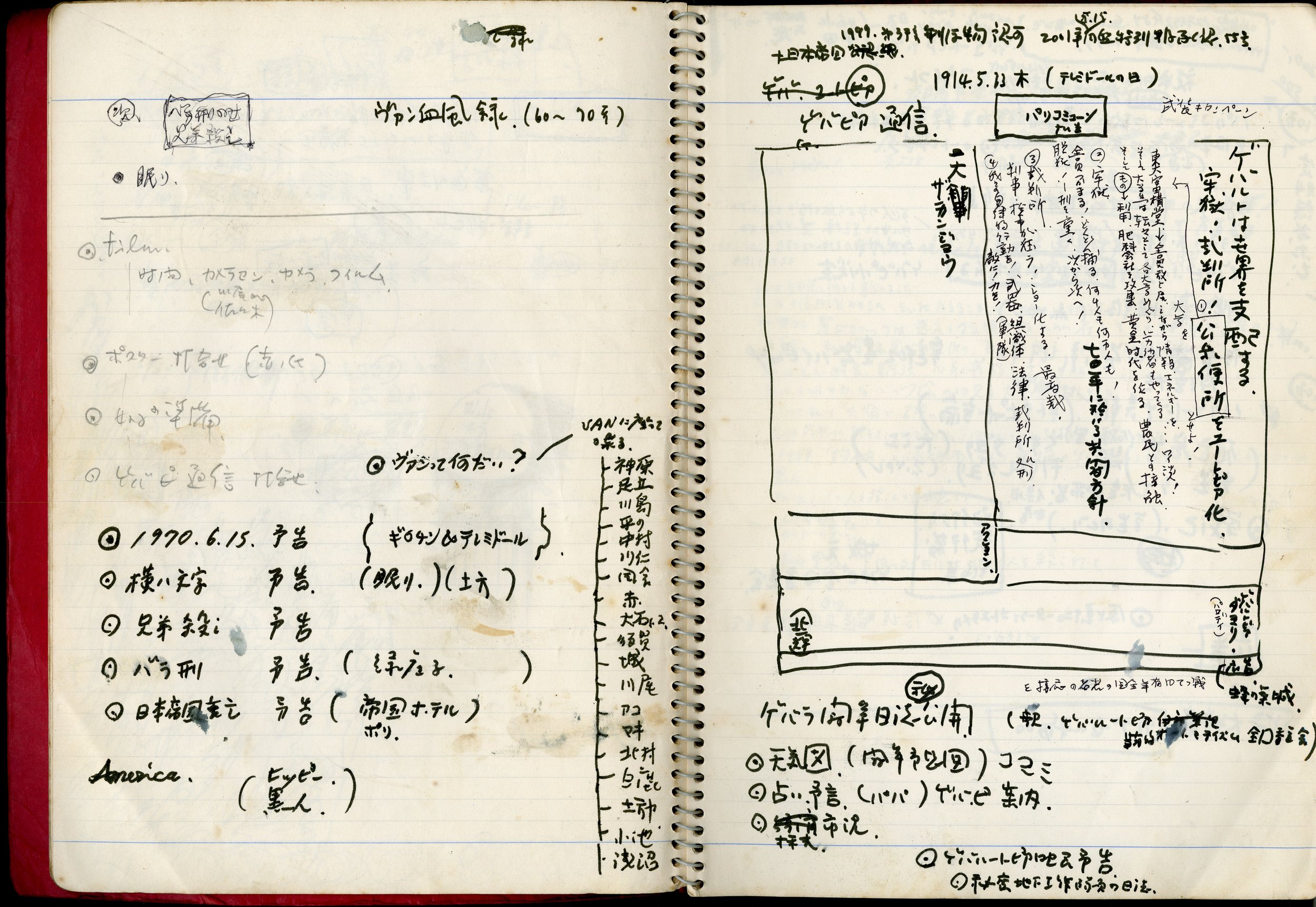

These two works should be considered as a series, although they are not directly linked. Another exploration of incomplete expression, beyond the concept of film or video art, was carried out in WOLS (1964-1969), featuring a series of stills of works by Informel artist Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze (known as Wols), Nihon University Public Collective Bargaining, (Nichidai taishū dankō, 1968), and Shinjuku Station (Shinjuku sutēshon, 1968-1974), leading to the Gewaltopia series, which used a similar approach to superimpose scenes of struggles and uprisings on university campuses and in city streets.

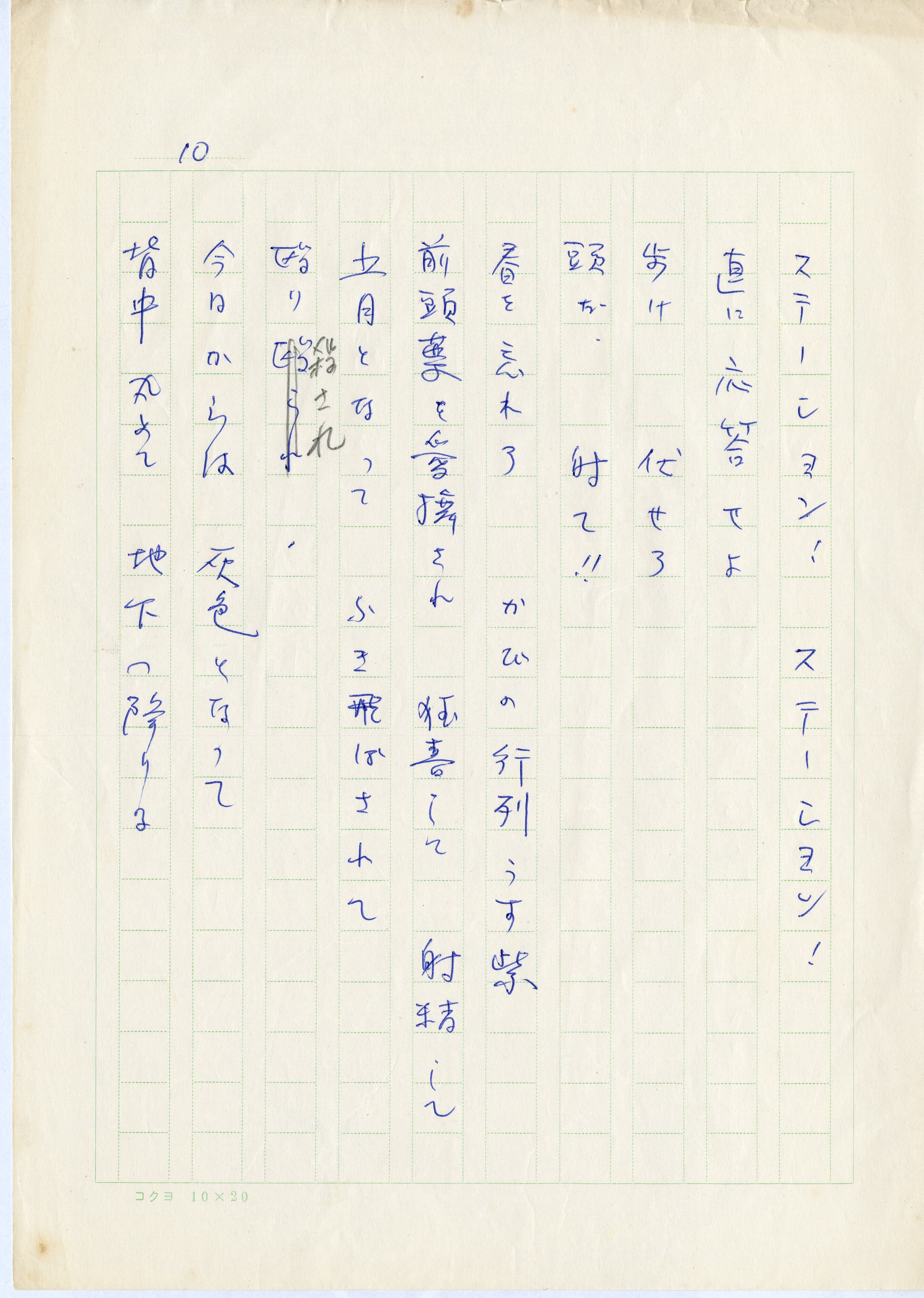

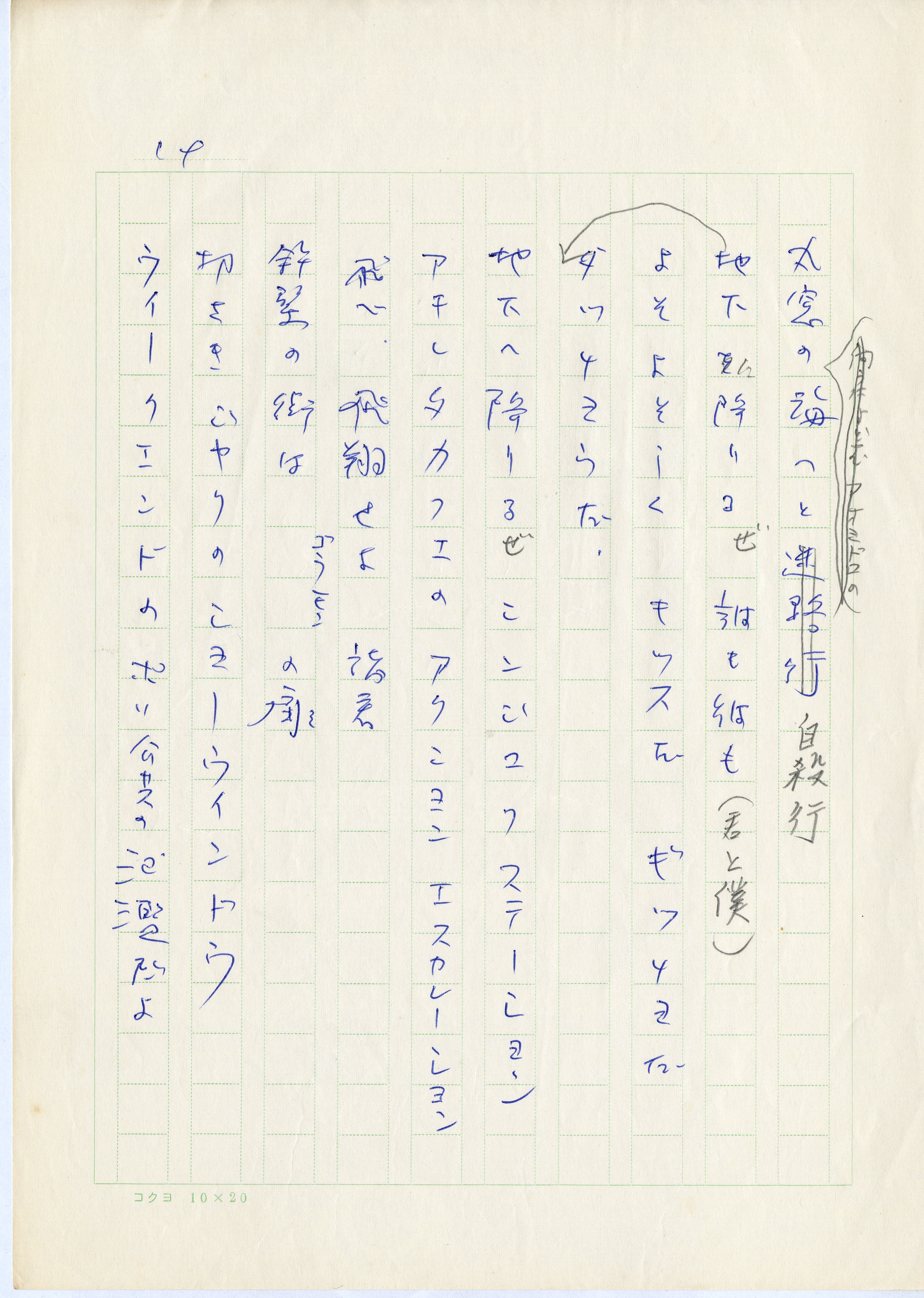

3. Gewaltopia

Jonouchi directed his camera at Japanese universities as the student movement gained fresh impetus around 1968. This series of works began with Nihon University Hakusan Street (Nichidai Hakusan-dori, 1968), which documented the first demonstration that took place in front of the Nihon University Faculty of Economics, in May, 1968. It continued with Nihon University Public Collective Bargaining (1968), then documenting barricades at the Nihon University College of Art in Nihon University College of Art Lecture Hall (Nichidai gei kōdō, 1968), to Gewaltopia Trailer (Gebarutopia yokoku, 1969), which connected his own works and the world of horror movies with protests at the University of Tokyo and Nihon University, and Shinjuku Station (1968-74), which superimposed scenes of an uprising in Shinjuku on International Antiwar Day (October 21, 1968). At times there are continuous shots, but these works are primarily composed entirely of series of stills, so it is difficult to grasp what is occurring and where the camera is pointing. Hirano, a collaborator from Nichidai Eiken, discusses this methodology, which originated with WOLS, as follows:

It was interesting that a montage of a series of stills, a technique he [Jonouchi] was forced to adopt because there was no money (and therefore not enough film), unintentionally became his signature methodology ... the same can be said of his documentation of a mass bargaining session during the Nihon University protests. He shot the things and events he wanted to shoot, regardless of public reaction or comments on what was being shot, and he seemed to manipulate time and the sense like rubber, and sometimes turn reality into a parody. [6]

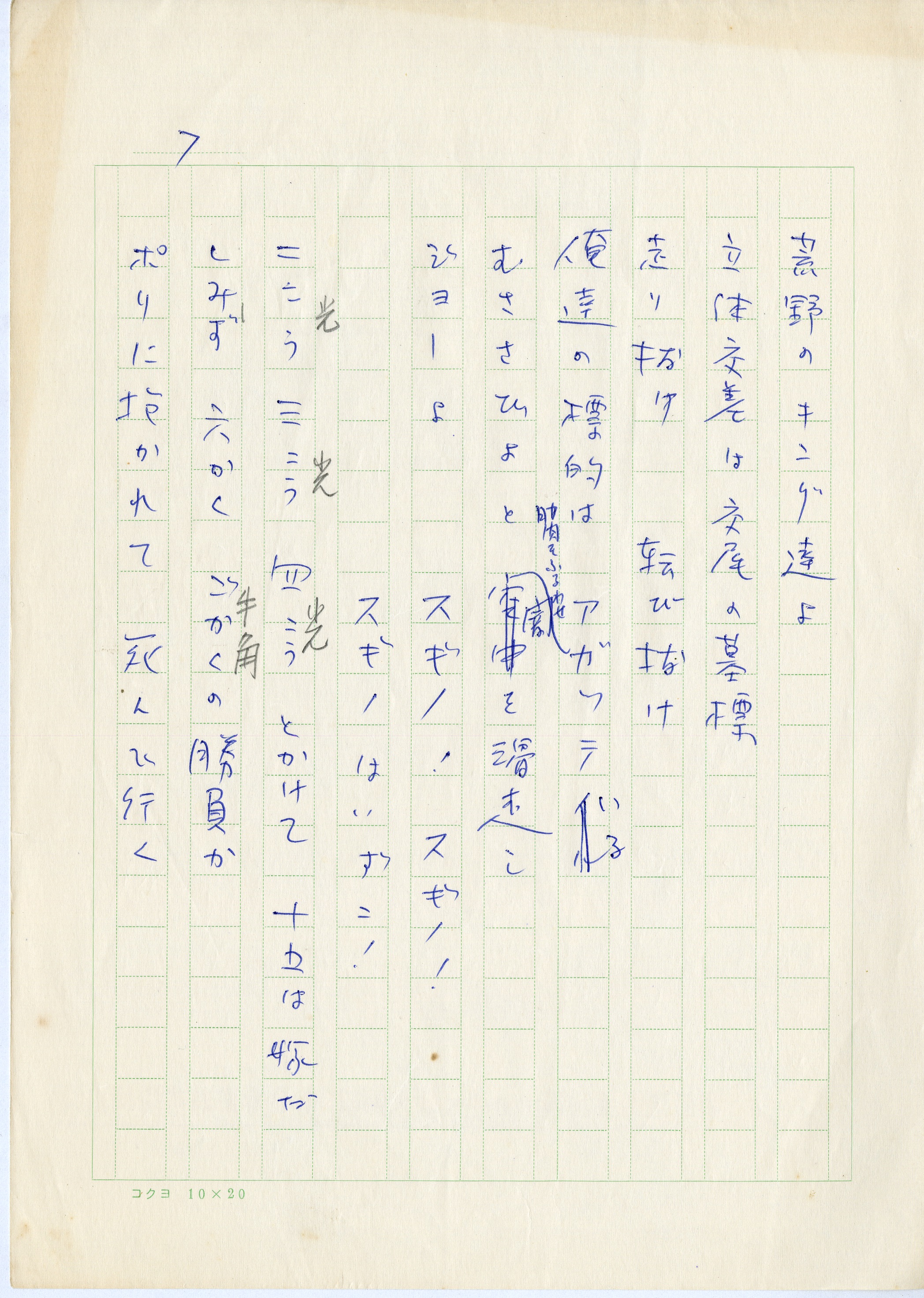

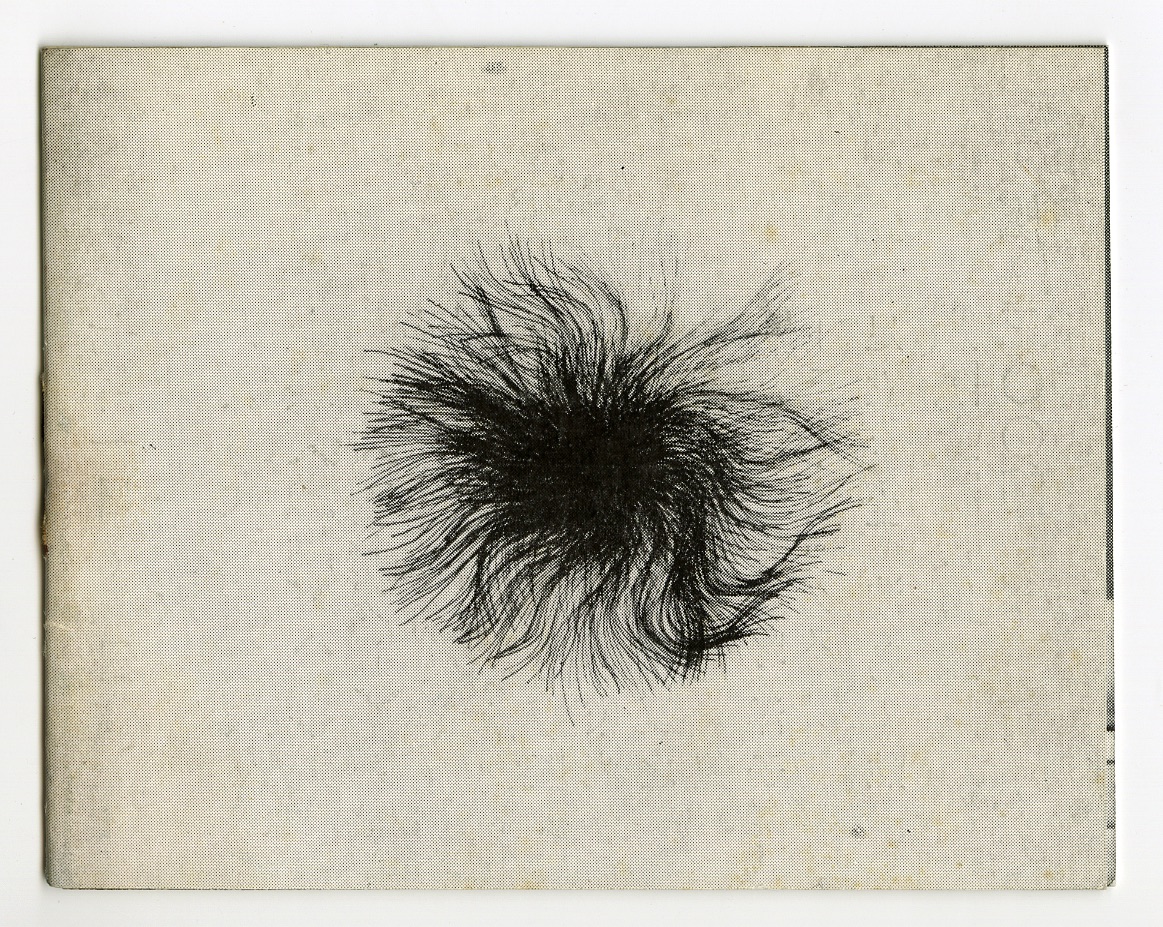

Rather than objectively documenting subjects while maintaining a certain distance from them, he caught on film the moments when struggles and uprisings erupt, as opposed to an overall picture of movement politics, by superimposing fragments of time and space caught frame by frame as he threw himself into the midst of situations in progress. So, each shot condenses what the protesters and rioters themselves saw, the scenery that unfurled before their eyes. Shot and shot, scene and scene, fragment and fragment, work and work are linked in organic relationships that totally differ in methodology from what we know as film or video art. And these relationships are further expanded, outside the cinematic establishment, in various experimental screenings. It is a new form of expression that cannot be described as film or moving image. In discussing the ∞ symbol, meaning infinity, Jonouchi predicts the death of existing cinema, and declares that he is moving toward a new world of the image he calls Gewaltopia.

Sweep aside…. retinal afterimage phenomena and 24-frames-per-second reality

Blow away… my pathology, my unstoppable delirium, my final fate

Disappear from this world… the frozen coffin, the dead world of the silver screen!

I will drift on the currents of life! [7]

Each of the works in the Gewaltopia series has “Gewaltopia” in its title, and Gewaltopia∞ was conceived as the collective title of the entire series. Works not from the series were also screened under this title at times. Therefore, while it is possible to discuss each as a separate work, there is no doubt that this disregards Jonouchi’s intention to move into a new world of the image. Also, under the circumstances, it seems likely that there was much material that went unedited and was never converted into finished works. Jonouchi wrote as follows in an announcement of a screening in 1976, also explaining its background.

All of my works shown here are from the group of works collectively referred to as Gewaltopia, although they represent only a small portion of this series. Their meaning is strongly related to Gewalt [German for “force” or “violence,” but usually used in Japan in reference to violent left-wing student protest and clashes with authorities], as is clear from the portmanteau word combining Gewalt and Utopia. I cannot deny that there was a powerful, passionate dedication to a Utopian ideal that had gone in a dark direction, and it became a rejection of Utopia, a sick hallucination, a lovers’ quarrel, a great misunderstanding, a piece of Dada, a paranoid fever, a stigmata, a void within a void. This is aptly summed up by the statement by the werewolf of philosophy, Emil Cioran: “To me humanity is a bad habit, each of us are sacrificed to the dreams of others, becoming sacrifices in a real sense in realizing the Gewalt-Utopia we have imagined, and after that, treading the long path of atonement.”

The original idea for Gewaltopia sprang from the “infinite film” screened at the ultra-fantastic interactive event organized by Yoshida Yoshie in the mid-1960s. The aim was to liberate the entire space with an infinitely rotating image.

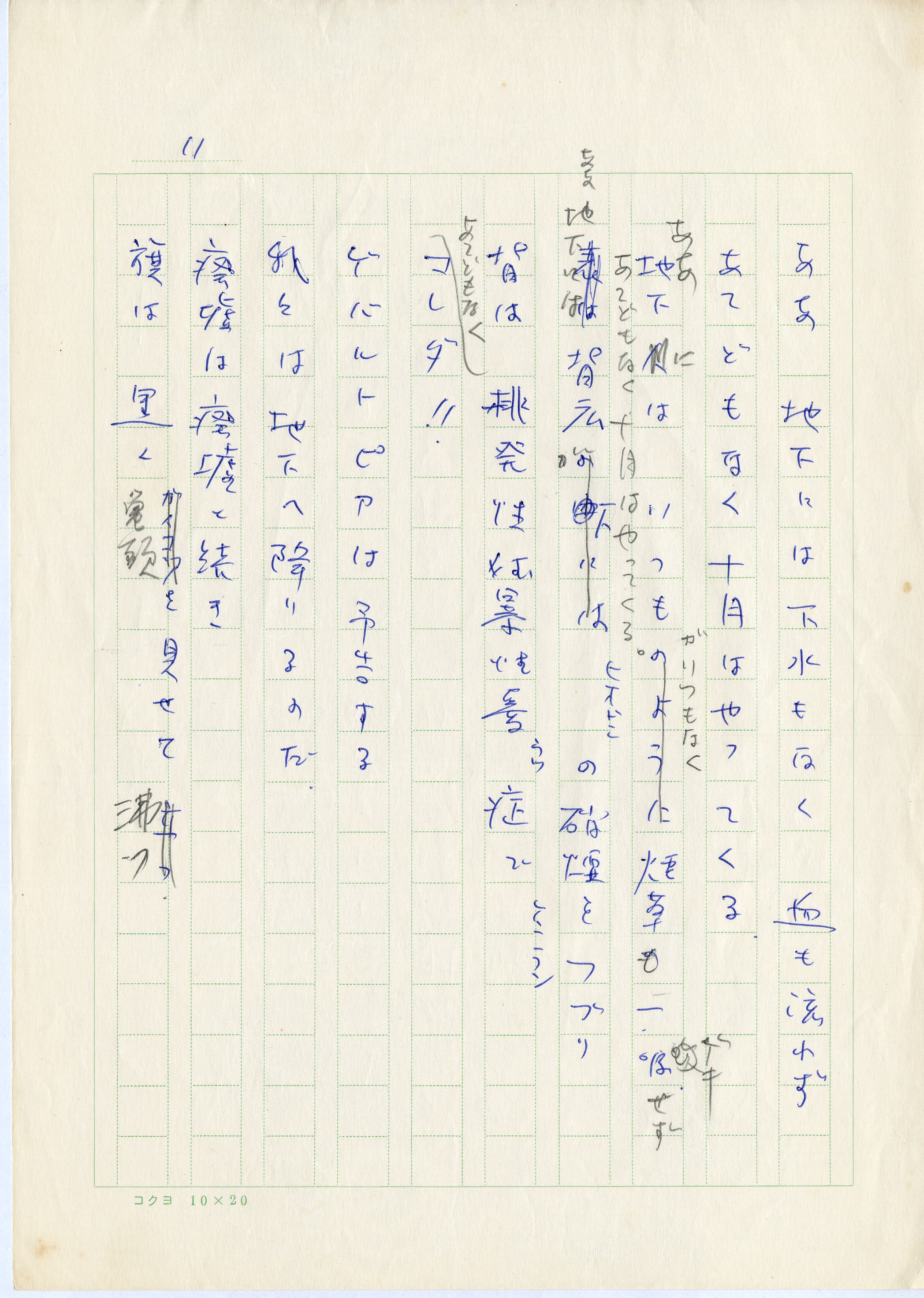

Also in the 1960s there was an experimental screening of “infinite films” at a film-viewing event organized by Ishizaki Koichiro, and Gewaltopia was crystallized in infinity. I had nothing to do with producing the films, that is, film abandoned on the side of the road or in warehouses was screened as “my” work – this was another occasion for regurgitating and chewing over dreams – and during the screening there were whips cracking and blood flowing, the audience was tied up, and Donald Ritchie pissed himself. However, the most primal Gewaltopia action was the “black mass” organized along with Kanbara and others starting in 1961 in preparation for the 6/15 gathering. The film became a great nightmare that filled the venue. The most metaphysical realization of Gewaltopia came out of a decrepit studio in 1962, a soft, limp feather of a film, an immaculate conception in an enclosed space, conceived and soon miscarried. At least 10 of a cycle of films I shot without rhyme or reason, over a decade starting in 1964, have vanished. In any case, Gewaltopia has come to haunt us in unforeseen ways over the past decade, as a labyrinth formed of its own translation, a symbolic magnifying glass, a displaced dream, a metaphysical spectrum, nonsense, Dadaist action, apostasy upon apostasy, unforeseen growth, ceremony of resurrection, violence repeated until it becomes stale routine. [8]

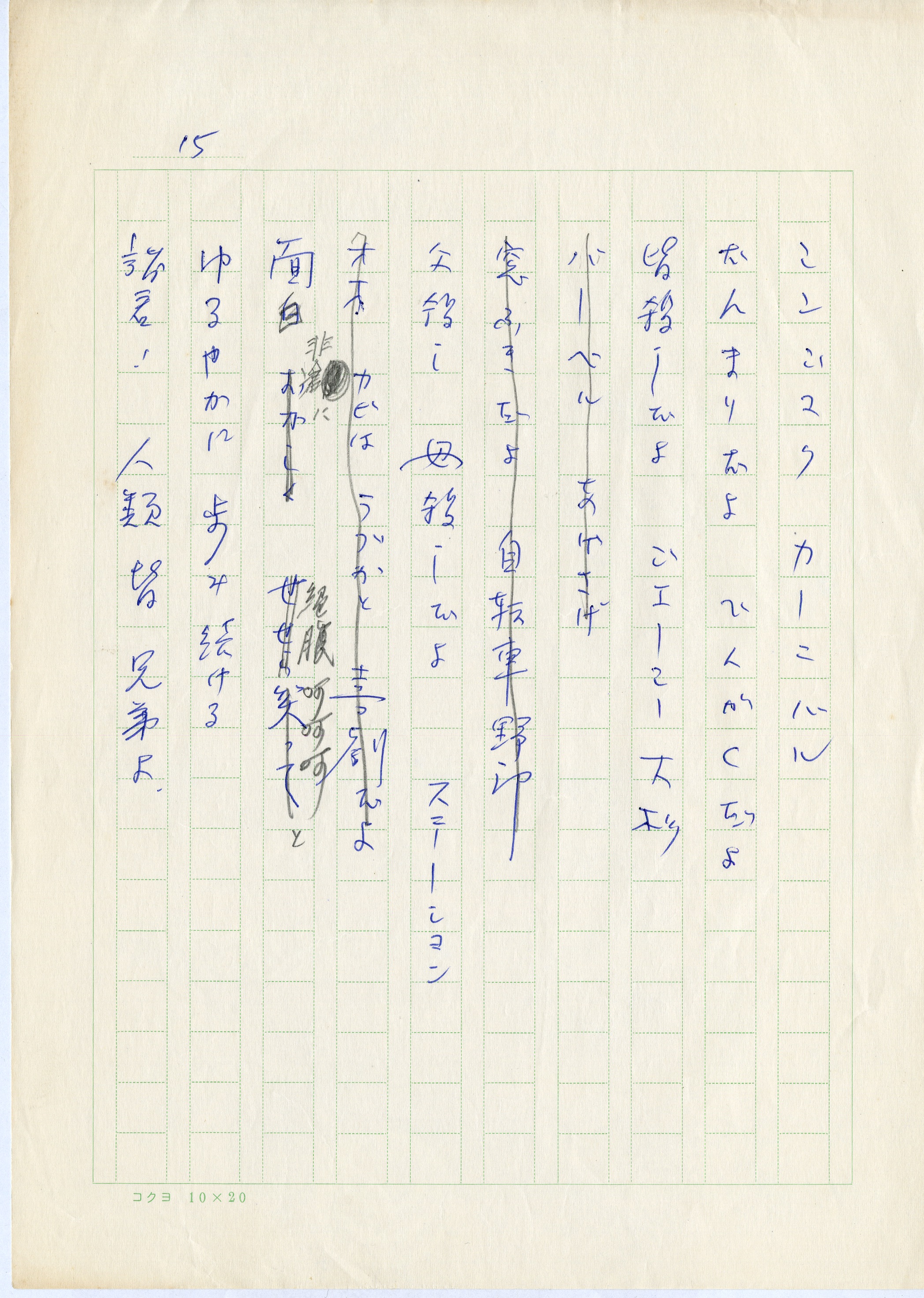

As with Document 6/15 and Shelter Plan, this series also consisted primarily of performance/screenings, and even when audio exists, it is separate from the films. Shinjuku Station was shown in a similar fashion, but in 1974 Jonouchi filmed his own performance/screening, and the currently surviving edition is a re-editing of this newly created film. Katsu Kanai, who was also at Nihon University College of Art, but working as an independent film artist rather than affiliated with the Film Club, recalled the performance/screening of Shinjuku Station, which took place at the same time as the screening of his own work in October 1974:

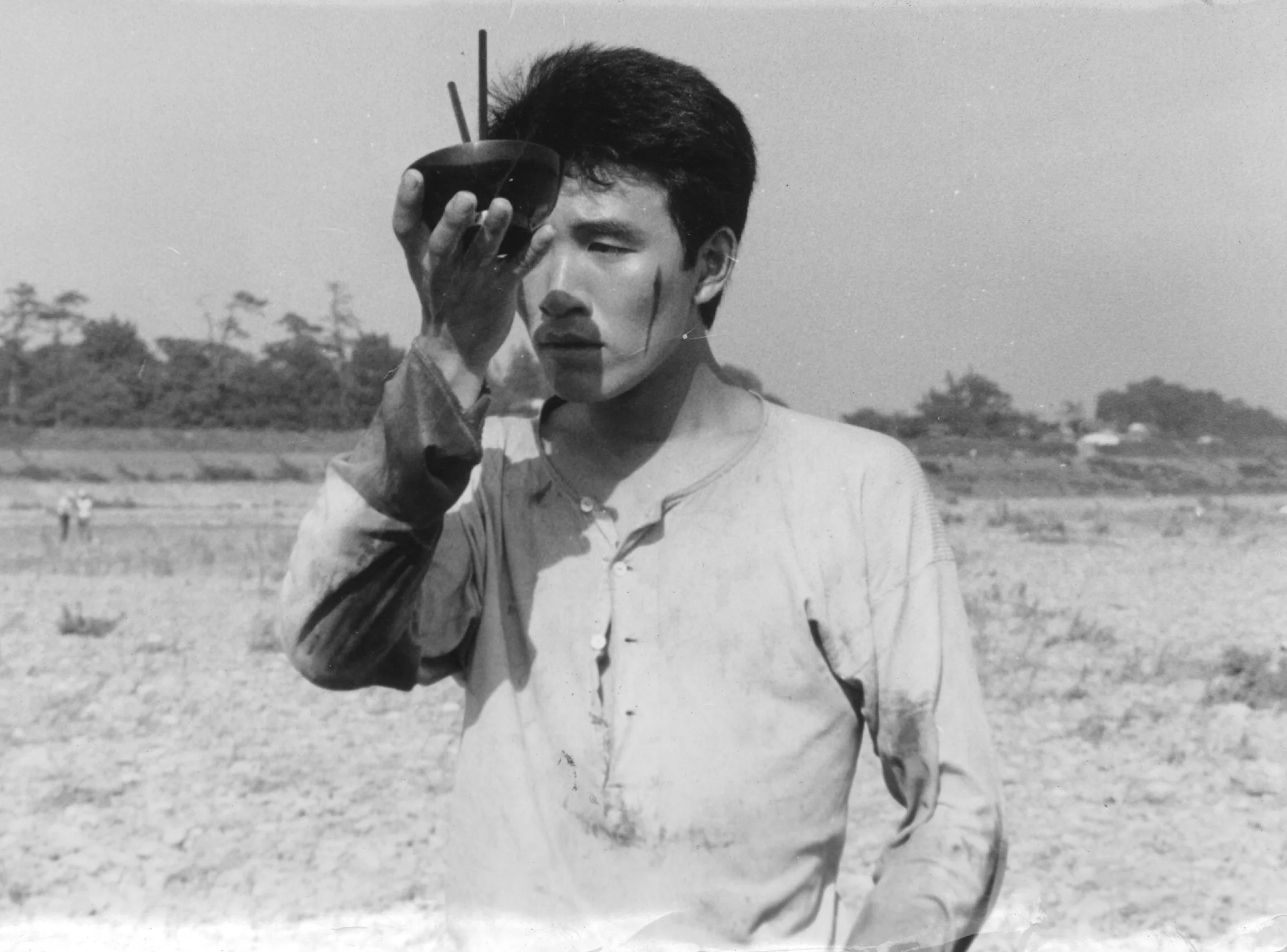

Jonouchi was dressed in what looked like a white safari outfit, and when he stood up, the first thing he did was forcibly screw something into the loop of his epaulet. It was a flashlight. I looked on dumbstruck as he called out to me in his usual loud, clear voice, “OK, here I come,” switched on the projector, and strode purposefully forward. The projected film was black and white footage of riot police and student protesters. It must have been October 21 in Shinjuku. Jonouchi screamed out, “Station! Station!” as he marched toward the screen, and when he reached a spot where the film was projected on his body, he began reciting poetry he had written. The flashlight stuck into his epaulet brilliantly lit up a notebook in his left hand. Meanwhile, his right hand made a repeated upward motion. What was it? The gesture, like beckoning, seemed to be casting some kind of spell. [9]

Kanai’s statement is an extremely valuable account by a contemporary, but it is not possible to compare the surviving version of Jonouchi’s work with the performances that preceded it based on this account alone. Kanai says the surviving version conveys “no more than 70%” of the performance/screenings (although many point out that 70% is quite a lot and certainly enough to make it worth watching), but, on the other hand, fellow VAN member and collaborator Asanuma says that an endless, ever-changing, never completed cyclical work is what Jonouchi’s experimental process was all about:

Some describe Shinjuku Station as “the ultimate in film performance.” This is partly thanks to Jo-chan’s [Jonouchi’s] acting and frenetic poetry recitation, but it also has to do with repetition: he stages a performance during or before the film, films that performance, and then screens that and again does a performance before the film, and on until it becomes an infinite kaleidoscope. This is one manifestation of what he describes as “the nature of all film lying in the generative process,” but his particular labyrinthine world is one that no other filmmaker has ever explored. [10]

It is virtually impossible to interpret Jonouchi’s practice in the conventional context of either film or art. However, when we experience his “works” outside of all such frameworks, they are not only intriguing experiments in Expanded Cinema, but reveal many new latent possibilities of film as a generator of one-time-only events.

1 Motoharu Jonouchi, interviewed by Takashi Nakajima, “The Origins of Student Film and the Nihon University Film Study Club,” Image Forum, October 1986, pp.147-148.

2 A Lunami Film Gallery postcard announces, “At the Imperial Hotel, presenting a happening/film by VAN Film Science Research Center, featuring Genpei Akasegawa, known for the 1,000-yen bill incident, and many other artists and musicians.” It describes the film as being 30 minutes long, but it is actually 25 minutes.

3 Motoharu Jonouchi , Koichiro Ishizaki, Lunami Film Gallery, 1967, p.1.

4 Motoharu Jonouchi, Koichiro Ishizaki, Lunami Film Gallery, 1967, p.1.

5 Motoharu Jonouchi, interviewed by Takashi Nakajima, “The Origins of Student Film and the Nihon University Film Study Club,” Image Forum, October 1986, p. 149.

6Katsumi Hirano, “Starving Ones, Return to VAN!” Underground Cinematheque, no.29, p.2.

7 Motoharu Jonouchi, "Ginmakuyo shine! --yokohachimojiron josetsu--," Kaku, p.20

8 Motoharu Jonouchi, “Notes on Works,” Underground Cinematheque, no. 29, p. 21. Jonouchi wrote about his own works, shown in Underground Cinematheque no. 81, a special 13-day screening starting on March 7, 1976. The films discussed are Gewaltopia∞ (part 1, 16mm, 80min, 1964-75), Trailer, WOLS, Imperial Hotel, Backdrop, The Sky, Lovers, LSD, Hijikata, Nihon University Lecture Hall, and Shinjuku Station.

9 Katsu Kanai, “Motoharu Jonouchi’s Technical Shinjuku Station,” “●,” Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, p. 45.

10 Naoya Asanuma, “Jo-chan and Invitation to JASA,” Jo-chan ariki: Collected Writings on Motoharu Jonouchi, Shichigatsu-do, p. 39.

Go Hirasawa, Meiji Gakuin University (Tokyo)

Go Hirasawa is a researcher at Meiji-Gakuin University working on underground and experimental films and avant-garde art movements in 1960s and '70s Japan. His publications include Godard (Tokyo, 2002), Fassbinder (Tokyo, 2005), Cultural Theories: 1968 (Tokyo, 2010), Koji Wakamatsu: Cinéaste de la Révolte (Paris, 2010), and Masao Adachi: Le bus de la révolution passera bientot près de chez toi (Paris, 2012). He has organized more than fifty film exhibitions throughout the world, including Underground Film Archives (Tokyo, 2001), Nagisa Oshima (Seoul Art Cinema, 2010), Koji Wakamatsu and Masao Adachi (Cinematheque Française, 2010), Theatre Scorpio: Japanese Independent and Experimental Cinema of the 1960s (Close-Up: London, 2011), and Art Theater Guild and Japanese Underground Cinema, 1960–1986 (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2012).

This project is part of Japanese Expanded Cinema research, which is supported by the Andy Warhol Foundation.